August, 2019. As summer break came to a close and the school year approached ever-so-forebodingly, I sat myself down with my copy of The Things They Carried. My local coffee shop, bustling with passersby searching for relief from the heat, provided less than ideal conditions for my already-short attention span. Yet, with a flip of the cover, the voices dissolved into a faint background rumble, drowned out by O’Brien’s voice speaking to me, telling a story.

O’Brien’s straightforward yet captivating narrative serves a candid purpose: to recount his own experiences and allow his story and those of others to come to life. But even a simple read of his novel pulls you into his world, into the war, with all its triumphs and tragedies. War forces you to leave your whole life behind. War forces you to carry the weight of others: your infantry, your family, your society. But I continued to be left with questions. Why support war? Why not voice your opposition? Why not cross the river and abandon the nation that sends you to fight and forfeit your life?

As a South Korean, my life has been shaped by war and national identity. Bordered by one of the greatest international threats of our generation, a looming sense of anxiety is always present, the kind that makes my stomach drop whenever North Korea makes headlines. Korea suffers from a chronic state of paranoia, one plagued by waves of missile tests and nuclear threats. Reading The Things They Carried, I couldn’t help but think about the stories of battles and separation that continue to affect individuals today. I couldn’t help but think about how a war could change my life completely. Koreans have found their own remedy for this constant fear: nationalism.

Despite being a hub of technological development and cosmopolitanism, Koreans continue to hold onto their traditionalist practices, rooted in community and pride. Families gather annually to make dishes, the recipes of which go back generations. Mandatory military service has grown to become a rite of passage, one that reminds individuals of their duties as citizens. Our national anthem begins with the line, “‘Till the day mountains erode and seas dry, God will protect our nation.” For its facade as a rapidly developing nation, South Korea has remained extremely socially and culturally bound.

I looked up from my book and out the window beside me. Recent relations with North Korea, trade conflicts with Japan, and the Hong Kong crisis had all made this summer one of resurgence and blind patriotism. The flags that hung from sidewalks in celebration of our Independence Day now carried a new meaning, one that reminded passersby that country came first, that the only way to stay together was to protest. It was simply the right thing to do.

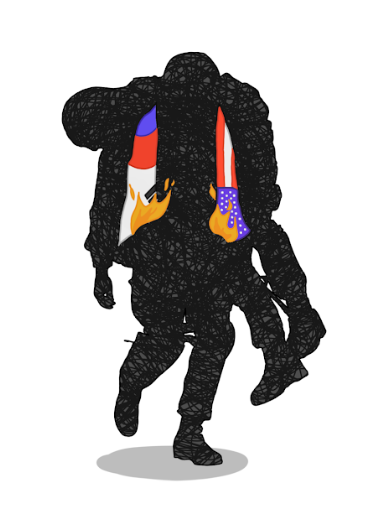

The term “blind patriotism” has a connotation of being rooted in discrimination and hatred, akin to fascism and extreme nationalism. But once you shed the layers of cultural overtones, it’s evident that blind patriotism affects societies in times of conflict and recovery. Blind patriotism fosters support for acts such as war and sacrifice, driving society to look down upon those who turn away from their country. The Things They Carried taught me that patriotism is a broken relationship between an individual and their nation. This exposes nationalism’s greatest weakness: it is blind to the individual’s story, leaving a husk of bravery and pride as its mark on history. Narratives like O’Brien’s are all too often lost to the wars themselves -— in giving into blind patriotism, one forfeits their identity as an individual beyond their nation. The Things They Carried taught me that the story of a nation is separate from the story of an individual and should be treated as such.

“Stories can save us… In a story, which is a kind of dreaming, the dead sometimes smile and sit up and return to the world,” said O’Brien. In writing his book, O’Brien does not ask his audience to reach any conclusion or moral. All he asks for is to bring his stories to life, to allow his experiences to impact a new generation of readers, moving forward in time. The modern American climate is one dictated by politics and widespread media, one where it seems that patriotism is the only common thread between us. Thus, nationalism has once again gained steam, branching off into xenophobia and support for the U.S.’s role in active conflict.

Blind patriotism is a political weapon that can divide societies and drive them to create a facade of morality or “rightness.” Constructive patriotism is a tool that can bring communities together under a common flag without erasing their individuality. The Things They Carried shows us that blind patriotism leads to a blind society. In reflecting upon O’Brien’s message to his readers, I ask the Deerfield community to consider the extent to which nationalism has played a role in our interpretations of history, narratives, as well as mainstream media. And, in doing so, allow the voices of the oppressed to breathe.