At the end of every term, Deerfield students and parents wait anxiously for the email notification that grades have been released. While grades should certainly not be the only drive for students to pursue academic excellence, many, including myself, cannot help but feel a rush of stress as they wait. And unfortunately, at times, I have been frustrated after seeing what my teachers deemed my numerical grades should be.

Granted, I will freely admit that some of these instances were caused by my own errors. However, other times, the grades I received on major assessments remained consistent, while my overall grade dropped. In some instances, I only received comments on major assessments. In these cases, I approached the teacher and was told that I was doing very well. But when my grade would be released, it would not seem consistent with the feedback I had received.

During the winter term of my ninth grade year, I obtained a grade I was proud of in a class but noticed that the class median was significantly higher than the one that Deerfield teachers tend to aim for: 89-90%. In the spring, I worked as hard as I had during the winter. However, when my spring grades were released, I found that both my grade and the class median had dropped by exactly two points. Since the grades I received on major assessments that term had not significantly changed, I figured this decline must have been due to a drop in my participation grade. I found this very odd, as my teacher had actually remarked in my course comments that my participation and collaboration skills had improved during the spring.

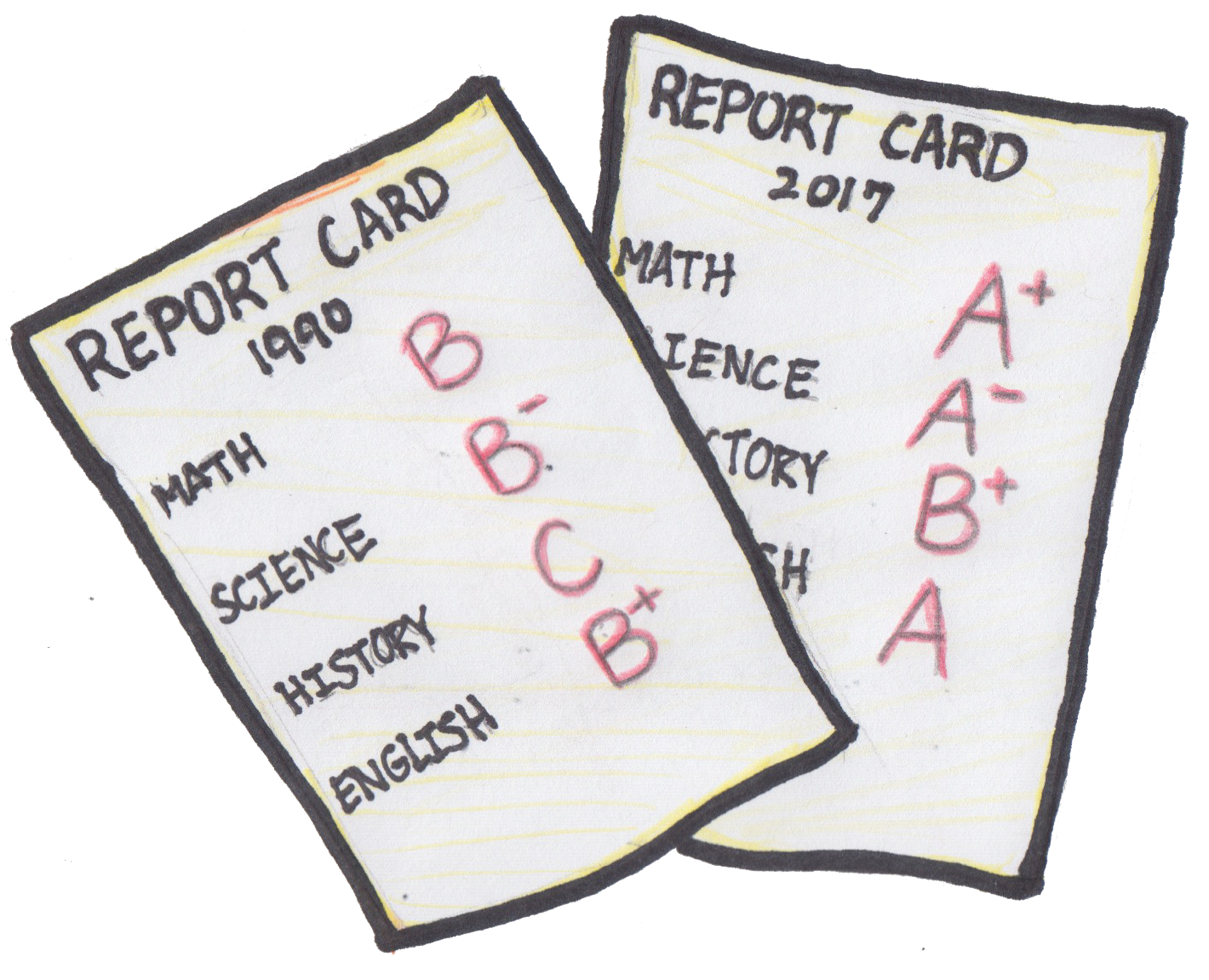

I have also noticed discrepancies in grades based on subjects. For instance, in a math or science class, the highest achiever could have a 98% or 99%, whereas top grades in the humanities generally do not exceed 95% or 96%. While I do understand that success in math and science is easier to quantify and writing a “perfect” essay is arguably impossible, I still think that the gap between the grades of top students in the humanities and those in STEM may give the impression that the STEM students are more academically driven and talented, when both have equal merit.

Many argue that every teacher has a different teaching style and that grade inflation at Deerfield has to be mitigated. To address the former point, in this piece, I am not trying to encourage the notion that every teacher must teach in one standardized way. I do believe that the diversity of the faculty at Deerfield is something to be very proud of. However, the subtle differences in teachers’ pedagogies cannot be determined from a numerical grade.

For example, a 92% in a particular English class may actually be the highest grade in a certain class, but a student may not able to discern this just from the grade. Even if the student were to approach the teacher and receive feedback that he/she was doing very well, at least in my experience, teachers do not often reveal the highest and/or lowest grade in their course. Thus, a student with a 92% may feel as if he/she is not performing at as high of a level as a student who has a different teacher and a 94% overall. A grade should be a clear indicator to students how they are are performing in a class for their own personal knowledge; however, I do not believe our current grading system allows for this kind of lucid communication.

As for grade inflation, I do not seek to deny the salience of it in this piece and I am aware that it is a phenomenon not only occurring at Deerfield but also at our peer schools. However, I do not believe that pursuing a policy in which every class must adhere to an 89% or 90% median is right. I do not think that every Deerfield student puts forth the exact same amount of effort or performs at the same level. In some classes, the students as a whole may demonstrate ability that is significantly above average. In this case, is it right to continue to enforce an 88% median? Or say that in another class, it is widely known to students that earning a grade above 92% is nearly impossible. How then, may we encourage these students to perform at a level higher than 92%? Why would some exceptional students in this class try their best, if they knew that whether they put in 70% or 100% of their effort, they would still obtain a 92% overall?

Because of the faults in Deerfield’s current grading system, I think that a grading scale of 1-6 or 1-10 would be optimal. Phillips Academy Andover currently uses a grading system of 0-6, in which a 6 indicates “outstanding,” a 5 “superior,” a 4 “good,” a 3 “satisfactory,” a 2 “low pass,” a 1 “failure,” and a 0 “low failure,” according to the school’s 2016-17 profile for college admissions offices. Similarly, Phillips Exeter Academy uses an 11-point grading scale. By adopting this kind of grading system, the scenario in which an excellent STEM student receives a higher grade than an excellent humanities student could be avoided. For example, instead of giving one a 98% and another a 93%, both students could receive a 6. This system eliminates the misconception that a “perfect score” is attainable, as a 6 indicates outstanding work, not perfection. Additionally, situations in which the top students (who are taking the same course but with different teachers) receive differing numerical grades could be avoided. I believe that Andover’s grading scale also fulfills a grade’s original objective in a better way. A 6 is an undisputably outstanding score, whereas grade inflation has rendered a 0-100 point based system more ambivalent.

In short, I believe that the current Deerfield grading scale does not always allow for students to obtain a clear image of their progress in a class. Term end comments may provide more thorough feedback; however, they do not address the numerical inconsistencies that I have mentioned. By adopting a unique grading scale, Deerfield Academy would be able to address this vagueness and inconsistency more proactively.