Late last autumn, a pod of pink whales socialized with a herd of golden sheep around the cardboard recycling on every floor of Field. Outside, the leaves fell and the campus dulled to a bleak color. Boys decorated their dress with bright bow ties. Girls wore waxed olive coats and high brown boots en masse. By mid-November, a silent, social force incentivized most of the students to dress in a similar fashion.

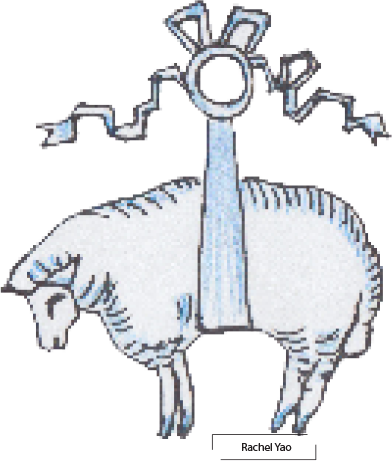

Deerfield demands dress. Ivied cravats adorn his tailored buildings. His bearded lawns, leafy locks, and flowery sideburns enjoy professional grooming; he upholds appearance well. His faculty and young patrons ape his etiquette out of tradition. The dress code prescribes that they sport a white-collar uniform he calls Class Dress. This Dress distinguishes Deerfield.

Deerfield demands dress. Ivied cravats adorn his tailored buildings. His bearded lawns, leafy locks, and flowery sideburns enjoy professional grooming; he upholds appearance well. His faculty and young patrons ape his etiquette out of tradition. The dress code prescribes that they sport a white-collar uniform he calls Class Dress. This Dress distinguishes Deerfield.

The word “class” partitions. It divides by value (e.g. academic subjects, class years, coach and business, upper, middle, and lower socioeconomic classes, etc). This is not exclusive to Deerfield; our society harbors the human habit of dividing the world into parts.

At Deerfield, Class Dress sets limits to the terms male, female, student, faculty and staff. Males wear blazers, ties and dress shirts—no jeans and no facial hair. In the winter, a sweater instead of a sports-coat is permissible. Females wear two visible layers. They can wear blazers like the males; few want to, fewer do.

Regardless of what gender wears it, the sports jacket ostensibly implies authority, business, class, dominance, etc. The code enables one gender to wear the jacket because it explicitly commands one to do so and not the other. This may prove problematic when considering power dynamics in a classroom or around a sit-down table.

The code sets up the jacket-wearing males as the norm and anything else as the “other.” It ought to support treating our students equally. It should either urge that both genders wear the jacket or that they both wear two visible layers.

The code sets up the jacket-wearing males as the norm and anything else as the “other.” It ought to support treating our students equally. It should either urge that both genders wear the jacket or that they both wear two visible layers.

This discrepancy concerning dress propagates a subconscious message about differences between male and female students and faculty. The more we make one party different in our mind the more unequal it becomes.

It is my opinion that Class Dress socially and culturally “others” female students here. Last year, I asked a group of girls why they chose not to wear blazers. One student responded that blazers were not flattering to females. I respected her answer but countered it with these questions: Why is a blazer, the symbol authority in our society, flattering to a boy and not a girl? What does that say about Deerfield when we expect our boys to wear blazers and leave it as an unpracticed option for our girls? Besides its being a comfort issue, why do more girls choose not to wear our capitalistic society’s garment of power?

Our girls seem to dominate the academics. Last spring the majority of the senior awards went to girls. At this year’s convocation, the Cum Laude Society welcomed 13 girls and 1 boy. Our girls get the academic reputation but fall short of the major social recognition they equally deserve.

Last spring I witnessed a bagpiper leading our male’s varsity lacrosse team down to the fields. I enjoyed the music and the procession but was let down when the girl’s varsity lacrosse team did not get the same treatment. Instead, they made do with a boom box. Male varsity sports dominate our attention while female varsity sports do not.

I can kinda sorta understand why this is the case in the world outside Deerfield, but I cannot wrap my head around why it happens here. We say that we are a community and that our school spirit is strong. If it is that strong, then there should be enough Deerfield spirit to support both female and male sports regardless of the level and the sport. We should stop focusing our attention on male this and female that. Regardless of a student’s gender, any Deerfield student is a Deerfield student, and that’s all that ought to matter.

Class Dress “others” other people in our community.

I have only seen my father wear a suit twice in my life. The first time was when he was best man at my uncle’s wedding; the other was for my graduation from St. Paul’s School.

My father is a handyman. He cleans, fixes and tends to an apartment building in the Upper East Side. He wears comfortable sneakers that allow him to move up and down the building, dark green working pants and a light-green collared shirt with the building corporation’s name and logo on the front.

When I was a student at Columbia, I would visit him during his lunch hour. At first he felt the need to change into his normal clothes because he did not want me to see him as a worker. I told him that I was proud and that he should be too, and that having to change robbed time from his lunch (and from me).

My mother felt the same when she cleaned rooms at the Hotel Marriott in New Jersey.

Dress sets working staff apart physically, emotionally and psychologically. I am cognizant of this dynamic whenever I enter the dining hall. Students sit together in most of the tables, and faculty and staff eat separately; rarely do they all sit together. There exists no written rule about this social segregation, but it’s a phenomenon that prevails in our Class Dress community.

I once read a book that a former Deerfield student wrote about the staff that works at Deerfield, often behind the scenes. I thought to myself, “This is great.” Even greater still would be if we got to learn who these people are in person, through dialogue, through lunches and dinners with them, through their own words instead of through a Deerfield publication.

Concluding points: Deerfield is fettered to its Class Dress. It should at least consider making the dress more equal for students and leave gender out of it. As for the rest . . .