This fall, Northfield Mount Hermon dropped its football program, citing a decrease in interest due to potential injury concerns, especially concussions. All this comes against the backdrop of the recent revelations that these “brain bruises” lead to later life dementia and other mental illness. Deerfield has also been investigating concussions. With the recent use of IMPACT testing and more rigorous analysis of recently injured students, the school aims to support its concussed athletes as much as possible.

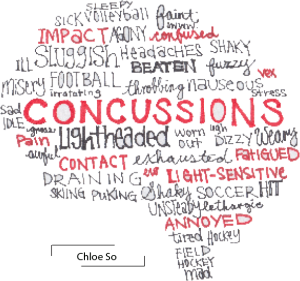

Robert Graves, head athletic trainer, has been observing and treating brain trauma in Deerfield athletes. “Concussions are pretty regular at Deerfield,” Mr. Graves said. “Depending on the season, we get, on average, at least 10 per athletic season. They don’t only affect students’ ability to play a particular sport, but also every area of their life. Some may feel all right, but upon cognitive exertion the student begins experiencing a headache, or sensitivity to light and noise, or fogginess.”

Robert Graves, head athletic trainer, has been observing and treating brain trauma in Deerfield athletes. “Concussions are pretty regular at Deerfield,” Mr. Graves said. “Depending on the season, we get, on average, at least 10 per athletic season. They don’t only affect students’ ability to play a particular sport, but also every area of their life. Some may feel all right, but upon cognitive exertion the student begins experiencing a headache, or sensitivity to light and noise, or fogginess.”

Many students, fearful of the potential consequences of missing class time and endangering future cognitive function, have grown fearful of playing contact sports such as football or ice hockey. Courtney Morgan ’16 dropped football this year after playing varsity last year. Morgan said, “My parents and I are worried about injuries, especially to my brain, and they don’t want me risking my head to play football.”

Fisher Louis ’16 recently left on medical leave after being diagnosed with his ninth concussion. At one point he even sustained three especially bad ones in a four-week span. “Since January,” Louis reported, “I’ve been having terrible headaches, which make it really hard for me to work, and sometimes read. I’ve visited several doctors to try to figure the problem out; I haven’t fully recovered because of stress from school and other reasons that the doctors aren’t sure about. One possibility is that my brain has gotten fragile, kind of like a bone that’s been broken a lot, and that now it’s really easy for me to sustain another concussion.”

Louis expects to return to Deerfield before the end of Fall Term, but will not return to playing contact sports, at the minimum, until next winter. Cases like this and research on the potential long-term effects of brain bruises have raised several questions. Namely, at what point should students stop playing contact sports?

Former Harvard football player and WWE wrestler; Chris Nowinski, now executive director of Sports Legacy Institute, which aims to solve “the concussion crisis by advancing the study, treatment, and prevention of the effects of brain trauma in athletes and other at-risk groups,” offered his opinion while speaking at Deerfield on November 4, saying “It should be a health concern. There is a fine line between playing sports competitively and lifelong damage. You have to weigh your options.”

According to Mr. Graves, “It is up to the discretion of the families. Doctors make suggestions, but generally when a sport begins to endanger a student’s future, then the athlete needs to consider switching sports.”

With a heightened awareness of the symptoms and outcomes of concussions must come a change at the very root of the problem—the playing fields. Mr. Nowinski stressed the importance of alerting medical technicians to the most common symptoms of concussion sustainment, including dizziness, imbalance and head pains.

Even Mr. Nowinski, while fulfilling his various professional athletic roles, fell prey to the detrimental athlete culture of minimizing a knock, which results in overlooked diagnoses. He recounted that after sustaining a head injury that, even “though [my] head was throbbing, [I] lied and said [I] was okay because [I] thought that was the only acceptable answer an athlete could give.”

An increase in data and analysis programs, as well as increasing awareness among students and school administrations, is sure to lead to a push for greater safety and a reassessment of programs.