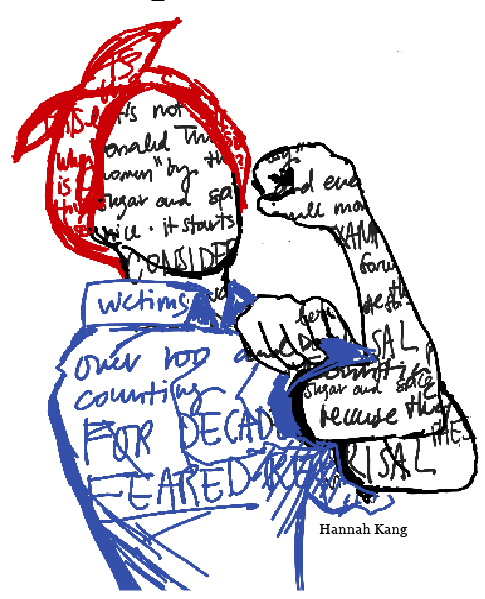

Over 100 and counting. That’s the current number of women who have come forward to accuse film producer Harvey Weinstein of sexual assault and rape. Sadly, as we all know, this isn’t the first famous man to be accused of sexual harassment or sexual assault. Roger Ailes and Bill O’Reilly recently confronted sexual harassment and assault charges. Then there’s Andy Signore, John Besh, Chris Savino, Robert Scoble, and Roy Price, just to name a few. And let’s not forget the tape where Donald Trump admits to grabbing women “by the pussy.”

So we can ask ourselves: Is this simply an epidemic among powerful men in our country, or is this a systemic and pervasive problem in our culture where male privilege perpetuates entitlement to whatever, whomever, whenever?

But let’s back up a little: to most women, it isn’t a surprise that so many victims have come forward or that so many victims waited to come forward for decades because they feared reprisal. It takes courage to speak up knowing that you’ll be accused of spreading financially motivated lies. A Huffington Post article, addressing actor Casey Affleck’s Oscar win and the sexual harassment allegations against him, speaks to this very issue.

The article reads, “Being white and male can be a powerful shield against failure, even in the face of evidence that perhaps a given honor is not deserved. And as actress Constance Wu pointed out in January after calling Affleck out, it is often those who speak out about alleged abusers that face a fear of repercussions as a result.”

These harassment and assault stories, however, are not isolated incidents and they don’t concern just a few famous men. As Wu points out, we live in a culture of “not believing” women, especially when they tell their stories about rape, assault, harassment, discrimination, or sexism. And it doesn’t just happen to women: it starts when a little girl is born — sugar and spice and everything nice. In our culture, “not believing” begins right away.

Consider these examples: a four-year-old girl (my sister) in preschool is terrified to go to school. Why? Because a preschool-aged boy is continuously poking her with thumbtacks. When teachers are asked to address the incident, it is dismissed, considered “harmless” because the boy was motivated by the fact that he “liked” the little girl.

It starts in small moments, like in elementary school, where my sisters’ voices weren’t heard, their needs not valued, when they went to the school administration asking for a change in playground space, as the boys had “claimed” every inch of the available blacktop. It starts when a boy told my sister that he was going to kill her and that she was ugly and fat before she was even old enough to explain the situation to the adults around her. Once again, teachers explained to my parents that this boy “liked” my sister.

This culture continues in high school, where a girl writes an opinion piece about the inauguration, which I did last year for the Scroll. While I believe in the importance of engaging in discussion with individuals who hold opposing opinions, the reactions to my article were not about creating a article were not about creating a meaningful dialogue. Instead, I was criticized for speaking out. The boys who approached me accused me of being too “charged.” Two emails in particular, sent to me by uperclassmen boys after my article was published, suggested that I was being disloyal to Deerfield. The goal was to intimidate me — after all, a sophomore girl couldn’t possibly have valid experiences and ideas of her own, so she needed to be taught a lesson. One email claimed that someone who held the views I held was “un-American” — simply because I, a girl, exercised a First Amendment right and suggested the possibility that misogyny could have played some role in the outcome of the election.

And, as is typical in situations where girls and women speak out, I was told by one of the emailers to “get over” it. More alarming was the response by the senior boy who warned me that “the world isn’t a ‘safe space,’” nor is it “always a pleasant place.” (A lesson that all female-identified individuals in this country already know all too well, thank you very much!)

However, I was lucky. There were adults around me at Deerfield that stepped in to help me navigate the situation. They didn’t sweep it under the rug or suggest that I had asked for trouble by writing a passionate opinion piece. And thank god they didn’t suggest that maybe the boys just “liked” me!

But I think about women in the workplace who do not have a single ally. These women face levels of sexual harassment and assault that I can’t even begin to imagine.

So with all the news circulating about sexual harassment and assault, I am forced to wonder what it must feel like to be a boy with privilege. Boys very rarely have to worry about their bodies being violated. They can walk through the world without fear of being catcalled or touched inappropriately. Most boys don’t know what it’s like to feel a man slip his hand onto your thigh on a subway in New York City. Most boys don’t know what it’s like to cross the street at night quickly because a man is walking too close for comfort. Boys are rarely told “the world isn’t a ‘safe space.’” More importantly, when they do speak out, they are often believed.

As more and more women come forward, we must ask ourselves how we can change our culture, our society. What can we do? This issue is not simply a “women’s issue.” Since the 1700s, our country has been carefully designed to keep women down and suppress their voices (just read the letter John Adams sent to Abigail Adams while formulating America’s government: “We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”) While it’s a true act of bravery for women to share personal experiences of harassment or assault or sexism, we need to do more. This can’t be said enough: we all know women coming forward with stories, and that means we also know the many men who are responsible for them. It is now time for accountability. It is now time for the presumption of “truth” and “believability” to be afforded to everyone.